The biggest exhibitions around the world in 2020

From Artemisia to Abramović, Old Masters to Olmecs, and Richter to Roman antiquities—here are next year's must-see shows.

Van Eyck: an Optical Revolution, Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Ghent, 1 February-30 April

Around half of the approximately 20 works firmly attributed to Jan van Eyck (around 1390-1441) will be gathered in Ghent for one of the largest exhibitions ever on the Flemish Old Master. The show will feature a number of freshly restored works, including the outer panels of the Ghent Altarpiece (1432) and Portrait of Baudouin de Lannoy (around 1438-40), which will come straight from the Berlin Gemäldegalerie’s conservation department. The Berlin restorers will have removed the old varnish and surface dirt, old retouchings and fillings, and will have applied up-to-date restorations of paint and a new layer of varnish. A relatively recent cleaning has also established Portrait of a Man with a Blue Chaperon (around 1428-30) as autograph. In addition, but involving no restoration, there will be a unique opportunity to see the two versions of the Madonna at the Fountain side by side (1439 from the Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp, and 1440 from the Frick Collection, New York). The exhibition will be complemented by myriad events as part of the Flemish Masters initiative (2018-20), a series of year-long programmes focusing on a different Dutch Master each year.

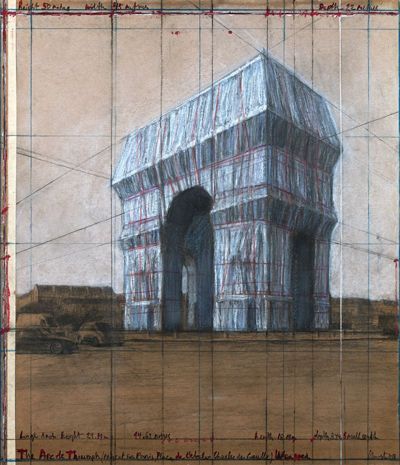

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 18 March-15 June

The Bulgarian-born French artist Christo and his late wife Jeanne-Claude first had the idea of wrapping the Arc de Triomphe when they rented a small flat nearby from 1958 to 1964. Their dream will come true this autumn (19 September-4 October) when the imposing monument will be shrouded in a silvery blue fabric, tied by 7,000 metres of red rope.

But before that, the Centre Pompidou will play host to the first institutional show on the duo in France, which will focus on the years they spent in the French capital. Previously unseen works such as Cratères (1959-61), a series influenced by Jean Dubuffet, will be included as well as a special focus on the Pont Neuf project, which, along with the Reichstag in Berlin, is one of the most famous landmarks the pair covered in fabric.

Since Jeanne-Claude’s death in 2009, Christo has carried on alone, but she remains a constant companion. In a recent interview in The Art Newspaper, he said: “She was extremely argumentative, very critical and I miss that so much. I always think when things become very difficult, what would Jeanne-Claude think now?”

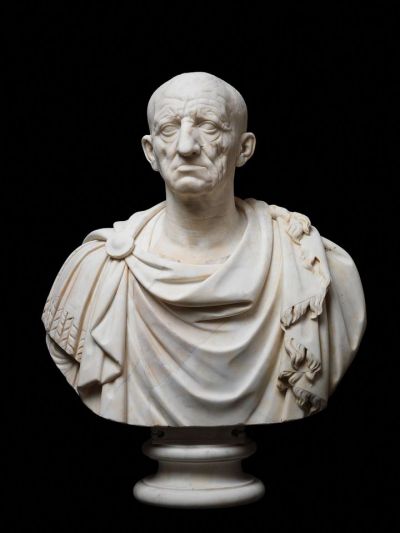

The Torlonia Marbles: Collecting Masterpieces, Musei Capitolini, Rome, 3 April-15 January 2021

A long battle between the Italian state and Alessandro Torlonia, who died in 2017 aged 92, has come to an end, and to celebrate the peace, 96 works from the family’s superb collection of 620 Greek and Roman sculptures will go on show this April, having been inaccessible for half a century. To emphasise the importance of the exhibition, not only is the Italian president due to open the show but the sculptures will spill out into the gallery housing Rome’s earliest collection: the bronze sculptures donated to the people in 1471 by Pope Sixtus IV, which include the Capitoline wolf feeding Romulus and Remus. The curator of the exhibition is Salvatore Settis, a noted classical scholar and former head of the Getty Research Institute, who mounted a ground-breaking exhibition on copies in classical sculpture for the opening of the Prada Foundation in 2015. He explains that the Torlonia show is of a collection that has incorporated earlier collections, right back to the 15th century. To gain the interest of the viewer without any classical education, he believes that the elegance of the display by the architect David Chipperfield will help a great deal, along with the fact that he has given the exhibition five stories to tell. Among these will be an evocation of the Museo Torlonia, which was open to the gentry from 1874 to the end of the 1940s, and a section about the pieces dug up by the Torlonia themselves on their huge estates. “We have also tried to put the pieces together in such a way that even a non-classicist asks questions,” Settis says.

Artemisia, National Gallery, London, 4 April-26 July

The first UK exhibition on Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1654) will focus on her singular position as a successful female painter in 17th-century Europe and how she turned it to her advantage. The show’s curator, Letizia Treves, says that the “very selective” presentation of 35 works at London’s National Gallery—including 29 paintings firmly attributed to Gentileschi—will invite visitors to consider “Artemisia in the round”, as a talented artist, storyteller, entrepreneur and “determined woman of wit and passion”.

The broad chronology ranges across the Italian painter’s 40-year career, “drawing attention to her adaptability to different markets and tastes in the cities where she worked”, Treves says. Trained in the Roman studio of her father Orazio Gentileschi, Artemisia established herself as an artist in Florence and returned to Rome in the 1620s before settling for the last 25 years of her life in Naples.

The museum’s recently acquired Self Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria (1615-17), which was unknown until it was discovered by a French auctioneer, will appear for the first time in context with star loans such as Susannah and the Elders (1610), Artemisia’s first signed work, and the unflinchingly bloody Judith Beheading Holofernes (1611-12). One room of the exhibition will explore images of the female hero, underscoring how Artemisia “brought an unprecedented female perspective to traditional subject matter”, Treves says.

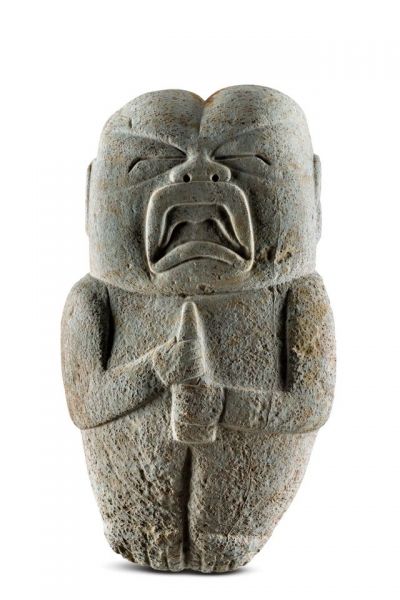

The Olmecs and the Cultures of the Gulf of Mexico, Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, 19 May-15 November

The Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac has joined forces with Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia to present the first major exhibition on the Olmecs in Europe. While the Olmecs, who inhabited southern Mexico from 1400BC to 400BC, are celebrated in the Americas, European audiences are less familiar with the Pre-Columbian civilisation than with the Aztec and Mayan peoples who came after them. The museum aims to bring greater recognition to the Olmecs by presenting a display of more than 200 artefacts that show their economic, social, political and artistic prowess as well as their development into the first major Mesoamerican civilisation.

The exhibition examines concepts such as symbolism, writing systems, ritualism and ideology that led to the creation of the Olmecs as a complex society, which, in turn, paved the way for the development of subsequent Mesoamerican civilisations. “The rise to social complexity is a rare event,” says Steve Bourget, the Branly’s head curator, who oversees its Americas collection. “It only happened in about six places in the world, and the process that took place in Mesoamerica is still poorly understood.”

Known for their colossal heads carved from stone, Olmec artisans also worked in clay, wood and jade. Scholars think this 40cm-tall figure of a baby holding an ear of corn may have been an offering to, or a depiction of, the god of maize, as the crop was a staple of the Olmec diet.

Masterpieces from the National Gallery, London, National Museum of Art, Osaka, 7 July-18 October

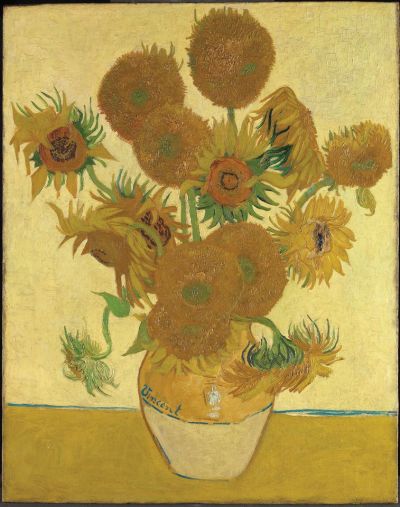

Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1888) is due to be shown for the first time ever in Japan alongside a selection of 60 other paintings from the National Gallery in London.

It is the largest assemblage of works from the UK museum to be loaned internationally and is timed to coincide with the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo. Japanese visitors can expect to see masterpieces that span the breadth of the National Gallery’s permanent collection, from the Italian Renaissance to the early 20th century, including pieces by Paolo Uccello, Diego Velázquez, Anthony Van Dyck, Claude Monet, J.M.W. Turner and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. As well as Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, stand-out works include Rembrandt’s Self Portrait at the Age of 34 (1640) and Vermeer’s Young Woman Seated at a Virginal (around 1670-72). The blockbuster will open in the spring at the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo (3 March-14 June) before travelling to Osaka in July. It will later travel to the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra (13 November-14 March 2021).

The show has been endorsed by Jeremy Wright, the UK’s former culture minister, who says that by sharing these treasures “we can promote the very best of Britain to the globe”. But more than just an exercise in cultural diplomacy, the show is expected to add millions to the London museum’s purse. Although unable to disclose the exact sum, a spokesman from the National Gallery says the exhibition fee “will contribute towards realising our strategic ambitions, including sharing our pictures with audiences in the UK”.

Gerhard Richter: Painting After All, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 15 August-18 January 2021

After a long absence, Gerhard Richter will return to US museums next year with his first major retrospective in two decades. The German painter, whose tireless experiments in form and format have made him a critical darling and auction house juggernaut, is due to present more than six decades of work at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles in August. It follows a version of the show that debuts in New York in the spring in what is due to be one of the final shows at the Met Breuer (4 March-5 July).

“He is one of the greatest painters of our time,” says Sheena Wagstaff, who is co-curating the Met Breuer show. “The twin modes of abstraction and figuration that he developed are now flourishing among younger generations of artists.”

The exhibition centres on the artist’s ground-breaking series lsuch as Cage (2006) and Birkenau (2014) while showcasing some of the painter’s earliest lithographs and other works not shown before in a museum exhibition. They include Group of People, a 1965 black-and-white painting from Richter’s early photo-based practice, which features a man reading a newspaper amid a crowd of demonstrators. Such works, says the curator, are a testament to not only the artist’s examination of art history but his engagement in the fraught political history surrounding it.

Marina Abramovic: After Life, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 26 September-8 December

You never know what to expect from a Marina Abramović show. Her 1974 performance, Rhythm 0, in Naples led a visitor to hold a loaded gun to her head. For her 2010 exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, she made prolonged eye contact with museum-goers. So what will the retrospective at the Royal Academy of Art (RA) bring? A spokeswoman said only that the artist will be in London for the run of the show and that the “exact nature of her presence is yet to be determined”. One of the confirmed works is Imponderabilia. First performed in 1977 in Bologna, it originally involved a naked Abramović standing in a narrow gallery entrance opposite her then partner, Ulay, forcing visitors to squeeze past them to get in. But Abramović will not be stripping for the RA show; instead, hired performers will stand guard. The exhibition will also feature new works that reflect on her changing body and the transition between life and death. “Abramović has been researching materials which can embody the idea of presence and absence, material and immaterial at the same time,” a spokeswoman says.

Raphael, National Gallery, London, 3 October-24 January 2021

The National Gallery in London will hold what promises to be one of the greatest ever exhibitions on Raphael with key loans coming from major museums including the Musée du Louvre, Vatican Museums and Galleria degli Uffizi. Among the paintings gathered for show will be Virgin and Child with the Young Saint John the Baptist, also known as the Esterházy Madonna, (1508) from Budapest’s Museum of Fine Arts and the Terranuova Madonna (1504-05) from Berlin’s Staatliche Museum, to be shown alongside the museum's own masterpieces such as The Madonna of the Pinks (around 1506-07). Altogether the museum hopes to assemble around 30 Raphael paintings, with 20 or so outside loans. The show will also include important drawings such as Study for the Head of an Apostle in the Transfiguration (1518-20), which had come to England in the 16th century and passed into the Chatsworth collection. It was sold in 2012 at Sotheby’s, fetching £29.7m, then a record price for a drawing and will be coming on loan from a private collection in New York. The exhibition will cover the entire span of Raphael’s career, not just paintings and drawings, but also his involvement in archaeology, architecture and poetry, as well as prints, sculpture, tapestry and the applied arts. There will be several shows this year marking the 500th anniversary of Raphael’s death, including another major show at the Scuderie del Quirinale in Rome (3 March-2 June).

Art at the Tudor Courts, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 6 October-10 January 2021

The late 15th-century Tudor dynasty, compared to royalty on the other side of the English Channel, were johnny-come-latelies. As upstarts, they were keen to prove themselves the equals of the more deeply rooted European dynasties, such as the tenth-century Valois, the 11th-century Habsburgs and Estes, or the 12th-century Colonnas. At the same time, the legitimacy of Tudor claims to the throne of England was itself shaky and their failure to produce multiple children did not add to their security. But, in order to keep up with the Joneses and materially to insist on their status, each successive Tudor monarch (with the possible exception of the short-reigned Mary I) collected and displayed works of art on a scale comparable to any other royal house. This exhibition shows the cosmopolitan range of their tastes from Henry VII’s seizure of the throne in 1485 to the death of Elizabeth I in 1603. Works by European armourers, goldsmiths, printers, manuscript illuminators, sculptors, painters and weavers, from both the Met’s own collections and from international loans, will be brought together to show what was the particular Tudor style. Among the highlights is Hans Holbein’s Portrait of Henry VIII of England (around 1537), on loan from Madrid’s Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza.

Nero: Life and Legacy, British Museum, London, 12 November-28 March 2021

Nero (AD37-AD68) is the archetypal villain, the Roman all students of ancient history love to hate. Any accomplishment he achieved in nearly 14 years as Roman Emperor—he was the last ruler of the august Julio-Claudian line—is overshadowed by tales of murder, debauchery, corruption and cruelty. Thanks to accounts by ancient writers such as Suetonius, Pliny the Elder and Tacitus, we know of Nero’s penchant for patricide, matricide and fratricide (basically, all the major “cides”), his sexual interest in both sexes (the more unavailable the better) and his mad extravagance. Nero’s taste for the finer things is best illustrated by his Golden House, which boasted surfaces made of gold, gems and ivory, a 120ft-tall statue of the emperor and a banqueting hall that rotated day and night. During the Great Fire of Rome in AD64, which destroyed two-thirds of the city, Nero reportedly played the fiddle while marvelling at “the beauty of the flames”.

The British Museum is attempting to separate fact from fiction in a 200-piece exhibition that explores contrasts in written sources and seeks to answer the question: who was Nero? A press statement asks if he was “an inexperienced ruler reconciling change in the face of political diversity, or a merciless, matricidal maniac?” We will have to wait and see.

Source: THE ART NEWSPAPER, 19th December 2019

Raphael's The Madonna of the Pinks (around 1506-07) © The National Gallery, London

Raphael's The Madonna of the Pinks (around 1506-07) © The National Gallery, London Old man from Otricoli © Fondazione Torlonia; Photo: Lorenzo de Masi

Old man from Otricoli © Fondazione Torlonia; Photo: Lorenzo de Masi Made the cut: Gentileschi’s Judith Beheading Holofernes (1611-12) is among the 35 works to be included in the “very selective” presentation © The National Gallery, London

Made the cut: Gentileschi’s Judith Beheading Holofernes (1611-12) is among the 35 works to be included in the “very selective” presentation © The National Gallery, London While the show centres on the series Cage (2006, above) and Birkenau (2014, right), it also examines early works such as Group of People (1965) © 2011 Gerhard Richter; All rights reserved

While the show centres on the series Cage (2006, above) and Birkenau (2014, right), it also examines early works such as Group of People (1965) © 2011 Gerhard Richter; All rights reserved The Frick’s Madonna at the Fountain (1440) will appear in the Ghent exhibition alongside a 1439 version from Antwerp Courtesy of the Frick Collection

The Frick’s Madonna at the Fountain (1440) will appear in the Ghent exhibition alongside a 1439 version from Antwerp Courtesy of the Frick Collection Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1888) is part of the largest group of works to be loaned internationally by the National Gallery. The show, which will coincide with the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, opens at the National Museum of Western Art before travelling to

Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1888) is part of the largest group of works to be loaned internationally by the National Gallery. The show, which will coincide with the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, opens at the National Museum of Western Art before travelling to A preparatory collage for Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s shrouding of the Arc de Triomphe this autumn Photo by André Grossmann; © Christo

A preparatory collage for Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s shrouding of the Arc de Triomphe this autumn Photo by André Grossmann; © Christo This 40cm-tall stone baby holding an ear of corn is thought to be connected to the Olmecs’ revered god of maize © Archivo Digital de las Colecciones del Museo Nacional de Antropología; INAH-CANON

This 40cm-tall stone baby holding an ear of corn is thought to be connected to the Olmecs’ revered god of maize © Archivo Digital de las Colecciones del Museo Nacional de Antropología; INAH-CANON Finding Nero: the British Museum’s exhibition features around 200 works—including this first-century AD copper alloy head—that seek to uncover the true story of the last ruler in the Julio-Claudian line Courtesy of British Museum

Finding Nero: the British Museum’s exhibition features around 200 works—including this first-century AD copper alloy head—that seek to uncover the true story of the last ruler in the Julio-Claudian line Courtesy of British Museum Holbein’s Portrait of Henry VIII of England (around 1537), on loan from the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid, will appear in the Met’s show © Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Holbein’s Portrait of Henry VIII of England (around 1537), on loan from the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid, will appear in the Met’s show © Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid Artist Portrait with a Candle is part of Abramović’s Places of Power (2013) series, which examined the connections between art and spirituality photo: © Marco Anelli; Courtesy of the Marina Abramović Archives © Marina Abramović

Artist Portrait with a Candle is part of Abramović’s Places of Power (2013) series, which examined the connections between art and spirituality photo: © Marco Anelli; Courtesy of the Marina Abramović Archives © Marina Abramović

Tweets by @ArtHaus_rs

Tweets by @ArtHaus_rs