JULIJE KNIFER’S ANTI-PAINTINGS MAKE A VIRTUE OF MONOTONY

When Yugoslavia broke with the Soviet Union in 1948, it jettisoned Socialist Realism in favor of its ostensible antithesis, modernist abstraction. The de facto state style of the 1950s and ’60s was what the literary critic Sveta Lukić called “socialist aestheticism”: an art-for-art’s-sake modernism that stressed formal experimentation above all else, projecting an image of enlightened liberalism as a counterpoint to Soviet dogmatism. Croatian artist Julije Knifer (1924–2004) responded to this affirmative milieu with black irony, riffing on geometric abstraction in “anti-paintings” characterized by a deliberately meaningless monotony. Knifer spent virtually his entire career painting a single motif: a meander pattern formed from interlocking right angles.

Knifer began painting the meander exclusively in 1959, around the time he cofounded the Zagreb-based proto-conceptual group Gorgona. Instead of a shared artistic program, the group’s members were linked by what they referred to as the “Gorgonic spirit,” a generally nihilist anti-art stance inspired by existentialist philosophy and the example of local prewar avant-gardes. Their most significant collective project was the “anti-magazine” Gorgona, publishing eleven artist-designed issues—including contributions from Dieter Roth and Harold Pinter—before the group disbanded in 1966; Knifer designed the second issue as a folded loop of connected pages with a continuous meander printed across them.

Titled, appropriately, “Meander,” the exhibition of Knifer’s work at Mitchell-Innes & Nash opened with two early pieces, displayed at the entrance, that show him in the midst of distilling his vocabulary, as if working out a problem. In the small, squarish painting Composition 15 (1959), stark black and gray geometric forms of different shapes and sizes create a sequence of right angles across the white ground. On the opposite wall, an untitled grid of thirty small framed collages (1959–61) displayed different configurations of linear black forms on white paper, spanning from an arrangement of vertical stripes to the prototypical meander: parallel verticals joined by narrow horizontal bands.

In the main gallery, nine paintings dating from the 1960s to the 1990s demonstrated Knifer’s exploration of the varied possibilities within his rigorously circumscribed schema. In BGS No. 3 (1973), for instance, the meander is a tight row of angular white bends sitting at the center of a black ground, while in the massive diptych Autumn XII (1993), the motif practically consumes each panel, resulting in near monochromes—one white, one black—edged by thin contrasting strips. Though Knifer limited himself primarily to a reductive black-and-white palette, the show included a handful of lesser-known works from a brief period in the late ’60s and early ’70s when he experimented with color, including an untitled painting from 1969, inspired by a visit to a Byzantine monastery, in which a meander hovers over

a shimmering gold ground.

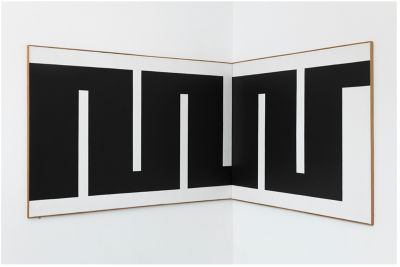

Knifer’s best works exploit the relationship between the pattern’s suggestion of infinite repetition and the boundaries of the canvas. In the triptych H.d. Tü tri v. 1975 I (1975), a black meander snakes across three adjacent panels, progressively expanding until it fills the work’s rightmost edge. Knifer cannily incorporated the seams between the panels into the composition: they are straddled by extra-wide vertical segments, and rhythmically echoed by the white lines that delineate the pattern’s bends. The meander escapes the frame entirely in Untitled (PM Gallery, Zagreb, Croatia), a re-creation of a 1988 wall mural, though the work lacks the compositional tension that animates architectural interventions like Tü E (Tuebingen Ecke), 1973, in which an unbroken meander, as if absorbing the contours of the room, winds between two canvases placed on adjacent walls in a corner of the gallery. While Knifer’s works are individually compelling, the exhibition makes clear that his meanders are most effective in aggregate, viewed as almost interchangeable segments of a single project. As he wrote in his koan-like 1977 text Notes, “I have probably already created my last paintings, but maybe not yet the first ones.”

Source: Artnews.com

Tweets by @ArtHaus_rs

Tweets by @ArtHaus_rs